2. 南京农业大学生命科学学院, 南京 210095;

3. 蚌埠医学院生命科学学院, 安徽蚌埠 233030

风化作用是指地表及其附近的岩石和土壤通过物理、化学和生物过程发生的变化和破坏。作为地表最重要的地球化学现象之一,岩石风化在很长一段时间内对土壤形成、元素地球循环和大气CO2浓度的调控具有重要作用[1-4]。微生物群落以及地衣是岩石的第一批定殖者,以单细胞或生物膜的形式存在,能影响矿物风化速率及土壤有机质数量与质量[5]。原位观察和微宇宙培养试验结果表明,微生物可以通过产酸、铁载体和金属复合配体、改变氧化还原条件和酸解作用来加速岩石和矿物的风化进程[6-8]。此外,菌体的粘附作用对矿物的生物风化也有很大贡献[9]。

不同岩石(矿物)(包括壁画、砂岩、石灰石、白云石、碳酸盐矿物、花岗岩、凝灰岩、玄武岩等)表生细菌群落分布、群落组成及相关风化潜能已有一系列报道[10-16];且岩石(矿物)表生微生物群落受岩石和矿物颗粒物理化学性质及当地气候条件的影响[17]。已有研究采用变性梯度凝胶电泳(DGGE)、X-射线光电子能谱等手段检测了不同来源凝灰岩表面生物膜中微生物群落结构及岩石中的真菌残体[18-20],而不同风化程度凝灰岩表生微生物群落与功能变迁的研究却鲜见报道。在本课题组之前的研究中利用可培养方法,从江西省抚州市东乡县不同风化程度凝灰岩及附近土壤中分离鉴定了可培养细菌,发现风化的凝灰岩表生可培养细菌从凝灰岩中溶出Fe和Al的能力更强,而土壤可培养细菌从凝灰岩中溶出Si的能力更强[21]。考虑到土壤可培养微生物仅占所有微生物的1%,由此可知得到的关于凝灰岩表生细菌群落及其生态功能的信息是有限的,而高通量测序技术的飞速发展则为环境中微生物群落的检测提供了革命性工具[22]。

深入研究岩石(或土壤)理化性质如何影响微生物群落多样性、结构以及岩石风化相关的功能,有助于更好地理解微生物群落在养分循环和土壤形成中的作用[22]。本研究分析了之前研究采集的不同风化程度凝灰岩样品和邻近红壤样品细菌群落结构与多样性、矿物风化潜能及对不同碳源的利用情况。以期进一步丰富凝灰岩的风化原理。

1 材料与方法 1.1 样品采集与理化性质分析于江西省抚州市东乡县(28°23′ N, 116°62′ E)采集了低风化(LR)和高风化(MR)凝灰岩以及邻近的红壤(SS)(粉砂亚黏土、铁铝土)[21]。该地区属于亚热带湿润气候,气候湿润、雨量充沛、四季分明、光热充足,生长期长。年平均气温19 ~ 21 ℃,年平均降水量1 600 ~ 1 900 mm。该地区主要岩石为凝灰岩,主要土壤类型为红壤。XRD分析显示此处凝灰岩和土壤样品的矿物组分主要包括石英、钾长石、高岭石、伊利石和蒙脱石,其中蒙脱石为LR样品特有矿物组分,而高岭石仅在MR和SS组样品中检测到[21]。不同风化程度凝灰岩和土壤样品性质如表 1所示。用于高通量测序和细菌群落代谢图谱(Biolog)分析的岩石(土壤)样品用干冰运往实验室后-80 ℃冻存。

|

|

表 1 不同风化程度凝灰岩和土壤样品性质 Table 1 Properties of weathered tuff and soil samples |

利用Fast DNA® Spin kit soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA)试剂盒从1.0 g岩石(或土壤)样品中提取总DNA,使用NanoDrop ND-1000分光光度计对纯化后的DNA进行定量检测,将符合要求的DNA于-80 ℃冻存。利用341F/805R对细菌16S rRNA基因序列V3 ~ V4区进行扩增[23],PCR产物纯化后利用Illumina MiSeq PE250平台进行高通量测序,原始数据于NCBI数据库获得登录号(PRJEB22180)。

1.3 高通量数据分析参考Sun等[24]的方法对高通量测序原始数据进行处理:原始数据质控后利用UCLUST对高质量序列进行聚类分析,将相似度大于97% 的序列定义为一个OTU;利用PyNAST以及RDP、Greengenes (GG) v 13_8_99数据库对OTU进行系统发育分析[24-25]。为避免测序深度不同对结果分析造成影响,每份样品抽取15 000序列进行后续统计分析。

1.4 统计分析选择独特OTU数目(OTUs)、Chao1指数、覆盖度指数作为指标来比较不同样品细菌α-多样性。基于Bray-Curtis矩阵距离利用PCoA分析来比较不同组样品间群落结构的差异;同时利用UPGMA法构建系统发育树来比较不同样品群落结构的相似度。采用Spearman相关系数来分析细菌群落α-多样性指数和优势种属与岩石理化性质之间的相关性。利用Tukey-Kramer HSD来检验不同处理间是否有显著性差异。

利用PICRUSt2软件包对不同风化程度凝灰岩及土壤样品细菌群落潜在的生态功能进行预测[26];并通过使用加权NATI指数计算样本中微生物与测序的参考基因组的相关程度来评估预测准确性并得到基于KEGG的通路预测。

1.5 利用Biolog微平板测定细菌群落的代谢谱利用96孔微平板(Biolog Inc., Hayward, CA)来分析不同岩石(土壤)样品微生物群落的代谢谱[27]。通过计算AWCD值来评估微生物群落对各种碳源的利用率,并通过计算香农指数来指征微生物群落的碳代谢多样性。利用主成分分析(PCA)解析不同样品底物利用模式,进而对微生物群落的功能结构进行表征。

2 结果与分析 2.1 不同岩石(土壤)样品细菌群落结构如表 2所示,在97% 相似度水平上覆盖度值均大于0.99,这意味着本研究的测序深度能代表绝大多数细菌群落,能满足后续分析的需要。独特OTU数目、Chao1指数在3组样品中的分布规律为SS > MR > LR,表明凝灰岩随风化程度的增加细菌群落α-多样性越高。

|

|

表 2 不同岩石(土壤)样品表生细菌群落结构与功能多样性 Table 2 Community structure and functional diversity of bacteria in different rock (soil) samples |

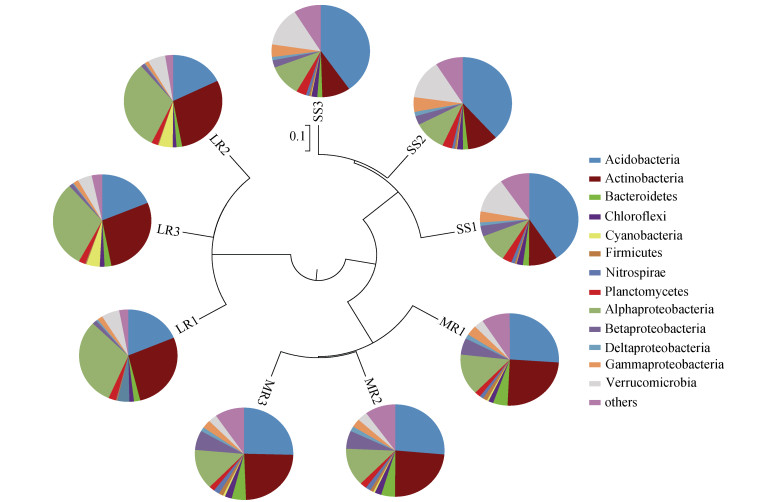

如图 1所示,UPMGA分析结果表明,不同风化程度岩石(土壤)样品聚类成两个分支,LR组样品单独聚成一支,MR组和SS组样品聚成另外一支,且MR组和SS组样品的3个重复也分别各聚类成一支。不同风化程度凝灰岩样品表生细菌群落结构显著不同,且低风化凝灰岩表生细菌群落与高风化凝灰岩以及土壤样品细菌群落结构差异更大。

|

图 1 不同岩石(土壤)样品表生细菌群落的UPMGA聚类分析及优势菌门(亚门)相对丰度分布 Fig. 1 UPMGA clustering analysis of bacterial communities in different rock (soil) samples and relative abundances of dominant bacterial phyla (subphyla) |

在门水平上,酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria,相对丰度17.8% ~ 40.7%)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria,9.2% ~ 29.2%) 和变形菌门(Proteobacteria,18.8% ~ 34.6%) 是该生境中的优势菌门。Acidobacteria和Gammaproteobacteria的相对丰度随着凝灰岩风化程度的增加而显著增加。相反地,Actinobacteria、蓝藻门(Cyanobacteria) 和Proteobacteria的相对丰度随着凝灰岩风化程度的增加而显著降低(图 1)。

在属的水平上,将相对丰度大于0.25% 的属定义为优势属。Bryocella、Gaiella、分支杆菌属(Mycobacterium)、嗜酸杆菌属(Acidiphilium)、甲基杆菌属(Methylobacterium) 为LR组特有优势属;全噬菌属(Holophaga)、大理石雕菌属(Marmoricola)、Oryzihumus、芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus)、苯基杆菌属(Phenylobacterium)、水居菌属(Aquincola)、马赛菌属(Massilia) 和假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas) 仅在MR组样品中检测到;浮霉菌属(Planctomyces) 为SS组样品特有优势属。

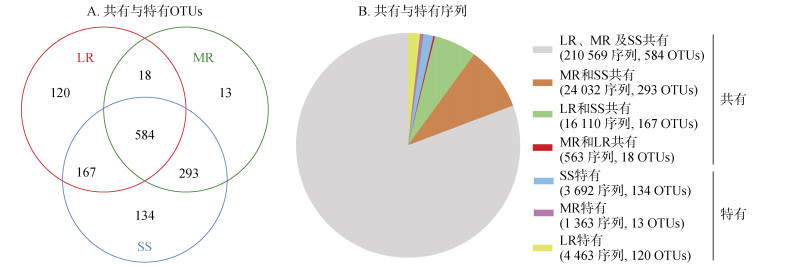

OTU水平上,特有和共有OTU在3组样品中的分布如图 2所示。1 329个OTU中有584个属于共有OTU,占总OTU的43.9%。这些共有OTU属于优势种,占总序列数的80.7%。而特有OTU大多为稀有种,SS组样品特有OTU最多,占总OTU的10.1%,其次为LR组样品(占总OTU的9.0%),MR组特有OTU数目占总OTU的1.0%。

|

(左侧为OTU韦恩图,右侧为韦恩图中OTU所包含的序列数) 图 2 不同岩石(土壤)样品表生细菌群落共有和特有OTUs(A)与序列(B)的分布 Fig. 2 The distribution of shared and unique OTUs (A) and reads (B) among different rock and soil samples |

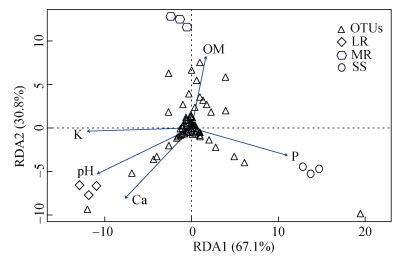

RDA模型共解释了99% 的细菌群落变异,其中轴1和轴2共解释了97.9% 的群落结构变异(图 3)。RDA模型分析中3组样品的聚类情况和PCoA分析结果一致。如表 3所示,细菌群落α-多样性指数与OM含量呈显著正相关,与有效态Ca含量呈显著负相关;Acidobacteria相对丰度与pH和Ca含量呈显著负相关,同时与OM含量呈显著正相关;与之相反,Actinobacteria相对丰度与OM呈显著负相关,但与Ca含量呈显著正相关;Alphaproteobacteria相对丰度与pH、有效态K和Ca含量呈显著正相关;疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia) 相对丰度与OM含量也呈显著正相关。

|

图 3 细菌群落与岩石(土壤)理化性质间关系的冗余分析 Fig. 3 Redundancy analysis of the relationship between bacterial communities and physicochemical properties of rock (soil) samples |

|

|

表 3 细菌群落α-多样性指数、优势菌门(亚门)相对丰度与岩石(土壤)性质之间的相关性 Table 3 Spearman's correlations between α-diversity indices, relative abundances of bacterial phyla (subphyla) and properties of rock (soil) samples |

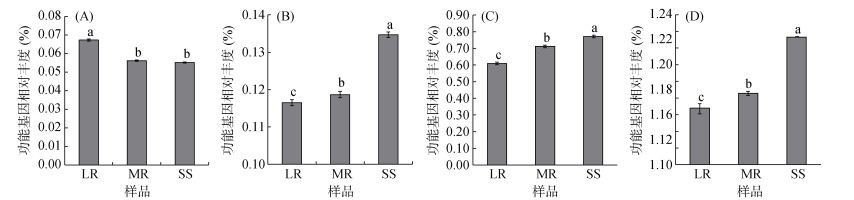

LR、MR和SS组样品的NSTI值分别为0.139、0.156和0.168。选取铁载体合成、碳酸酐酶、鞭毛合成和产有机酸这4个类群的功能基因丰度来评估不同岩石(土壤)细菌群落风化矿物的潜能。如图 4所示,编码鞭毛相关功能基因的相对丰度在3组样品中的分布为SS > MR > LR。SS组样品中编码碳酸酐酶和产有机酸相关功能基因的丰度显著高于MR组和LR组,LR组中铁载体合成相关功能基因丰度显著高于MR组和SS组,说明细菌群落可能通过多种机制来加速岩石风化。

|

(A. 铁载体合成;B. 碳酸酐酶;C. 鞭毛合成;D. 产有机酸。图中小写字母不同表示样品间差异显著(P < 0.05)) 图 4 与矿物风化相关的功能基因家族相对丰度的预测 Fig. 4 Inferred microbiome functions associated with mineral weathering |

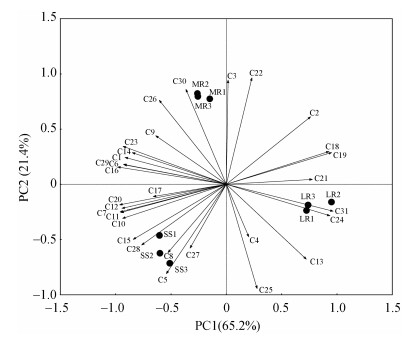

如表 2所示,SS组微生物群落的碳源利用率最高,其次是MR组,然后是LR组。另外,SS组和MR组微生物群落代谢的AWCD值和香农指数显著高于LR组。PCA分析结果表明,LR组、MR组和SS组样品微生物对碳源底物的利用模式具有显著差异(图 5)。LR组微生物群落利用更多的底物包括D-葡糖胺酸(C13)、衣康酸(C21)、L-精氨酸(C24)和腐胺(C31),而吐温80(C3)、α-酮丁酸(C22)、L-苯丙氨酸(C26)和苯乙胺(C30)则在MR组样品中被利用更多,SS组样品微生物群落则利用了更多的β-甲基-D-葡萄糖苷(C8)、D, L-α-甘油(C15)和L-苏氨酸(C28)。

|

图 5 不同岩石(土壤)样品微生物群落碳源利用情况的PCA分析 Fig. 5 PCA analysis of microbial community carbon source utilization in different rock (soil) samples |

本研究发现随着凝灰岩风化程度的加剧,表生细菌群落α-多样性也显著增加。伴随着凝灰岩的风化程度加剧,岩石中的Si、Al、K、Fe等结构元素不断溶出[21],并产生黏土矿物和腐殖基质,以可交换态和生物可利用的形式保留这些营养物质,从而孕育遗传和代谢多样性更为丰富的微生物群落。本研究还发现细菌群落α-多样性指数与OM含量呈显著正相关(表 3)。有机质含量的增加既为微生物活动提供了能源物质,同时也为酶促反应提供了丰富的底物。本课题组之前的研究中发现伴随着苔藓地衣等先锋植物的覆盖,钾质粗面岩的风化速率大大提升,且风化程度越高,表生细菌群落α-生物多样性越丰富[14]。Santelli等人[28]也发现,栖息在海底熔岩中的细菌的多样性和丰度与岩石风化程度呈正相关。

在本研究中检测到凝灰岩和土壤中细菌优势菌门为Acidobacteria、Actinobacteria和Proteobacteria(尤其是Alphaproteobacteria)(图 1);这与之前关于岩石(或矿物)表生优势细菌菌群的相关研究结果是一致的[29-32]。Actinobacteria和Proteobacteria经常在磷灰石、花岗岩、海底玄武岩、火山玄武岩、紫色粉砂岩、钾质粗面岩等岩石表面出现,表明它们对岩石和矿物表面的定居和栖息具有良好的适应性。另外本研究中Acidobacteria随凝灰岩风化程度的加剧在细菌群落中的占比越来越高,其中由凝灰岩风化形成的红壤中Acidobacteria的相对丰度最高,且Acidobacteria的相对丰度与土壤pH的相关性系数为–0.729(P < 0.05)。Jones等[33]发现Acidobacteria的相对丰度与土壤pH呈显著负相关。无论环境pH如何,细菌细胞内的pH都接近中性,并且细菌通常通过增加胞内缓冲能力或降低细胞膜的渗透性来增强其对酸性环境的适应性。Acidobacteria能通过共享相似的细胞结构来补偿适应低pH,比如与土壤pH呈负相关的一类新型支链甘油二烷基甘油四醚膜酯[34]。

先前的研究表明环境因素(比如栖息地类型和异质性)在形成细菌群落过程中发挥重要作用。一些限制性的营养元素(如P、K、Si、Al、Ca)的含量能驱动矿物表生细菌群落结构的变异[1, 35],特别是在贫营养条件下,岩石(或矿物)中限制性营养成分对不同组成的微生物群落的优先定殖具有选择性。本研究通过RDA模型分析也发现pH、OM以及有效态P、K和Ca的含量共解释99% 的细菌群落变异,是细菌群落结构的重要驱动因素。之前有研究报道pH可能起到了有效的栖息地过滤器的作用,即随着pH偏离中性越来越酸时,细菌群落成员谱系中隶属于Acidobacteria的重复序列就越来越多[36]。

4 结论从凝灰岩到红壤的风化过程中,随凝灰岩风化程度的加剧,pH不断下降而岩石(土壤)中有机质含量、表生细菌群落结构α-多样性与代谢多样性越来越高。Acidobacteria、Actinobacteria和Proteobacteria是不同风化程度凝灰岩(土壤)表生的优势菌门,Acidobacteria的相对丰度随着凝灰岩风化程度的增加而增加,而Actinobacteria和Alphaproteobacteria的相对丰度随着凝灰岩风化程度的增加而显著降低。岩石(土壤)的pH、OM含量以及有效态P、K和Ca含量共解释了99% 的细菌群落变异,是细菌群落结构的重要驱动因素,细菌群落α-多样性指数及Acidobacteria菌门的相对丰度与OM含量呈显著正相关。

| [1] |

Gleeson D B, Kennedy N M, Clipson N, et al. Characterization of bacterial community structure on a weathered pegmatitic granite[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2006, 51(4): 526-534 DOI:10.1007/s00248-006-9052-x (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Hilley G E, Porder S. A framework for predicting global silicate weathering and CO2 drawdown rates over geologic time-scales[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(44): 16855-16859 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Fang Q, Lu A H, Hong H L, et al. Mineral weathering is linked to microbial priming in the critical zone[J]. Nature Communications, 2023, 14(1): 345 DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-35671-x (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

赵越, 杨金玲, 许哲, 等. 模拟酸雨淋溶下不同母质发育雏形土矿物风化中的盐基离子与硅计量关系[J]. 土壤学报, 2023, 60(5): 1456-1467 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Esposito A, Ciccazzo S, Borruso L, et al. A three-scale analysis of bacterial communities involved in rocks colonization and soil formation in high mountain environments[J]. Current Microbiology, 2013, 67(4): 472-479 DOI:10.1007/s00284-013-0391-9 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Picard L, Turpault M P, Oger P M, et al. Identification of a novel type of glucose dehydrogenase involved in the mineral weathering ability of Collimonas pratensis strain PMB3(1)[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2021, 97(1): fiaa232 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Lemare M, Puja H, David S R, et al. Engineering siderophore production in Pseudomonas to improve asbestos weathering[J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2022, 15(9): 2351-2363 DOI:10.1111/1751-7915.14099 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

毛欣欣, 何琳燕, 王琪, 等. 具矿物风化效应伯克霍尔德氏菌的筛选与生物学特性研究[J]. 土壤, 2017, 49(1): 77-82 DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-3908.2017.01.015 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Gerrits R, Pokharel R, Breitenbach R, et al. How the rock-inhabiting fungus K. petricola A95 enhances olivine dissolution through attachment[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2020, 282: 76-97 DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2020.05.010 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Hobart K K, Greensky Z, Hernandez K, et al. Microbial communities from weathered outcrops of a sulfide-rich ultramafic intrusion, and implications for mine waste management[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2023, 25(12): 3512-3526 DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.16489 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Mugnai G, Borruso L, Wu Y L, et al. Ecological strategies of bacterial communities in prehistoric stone wall paintings across weathering gradients: A case study from the Borana zone in southern Ethiopia[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2024, 907: 168026 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168026 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Brewer T E, Fierer N. Tales from the tomb: The microbial ecology of exposed rock surfaces[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 20(3): 958-970 DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.14024 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Mieszkin S, Richet P, Bach C, et al. Oak decaying wood harbors taxonomically and functionally different bacterial communities in sapwood and heartwood[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2021, 155: 108160 DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108160 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Wang Q, Cheng C, Agathokleous E, et al. Enhanced diversity and rock-weathering potential of bacterial communities inhabiting potash trachyte surface beneath mosses and lichens - A case study in Nanjing, China[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 785: 147357 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147357 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Doetterl S, Berhe A A, Arnold C, et al. Links among warming, carbon and microbial dynamics mediated by soil mineral weathering[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2018, 11: 589-593 DOI:10.1038/s41561-018-0168-7 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Wild B, Daval D, Beaulieu E, et al. In-situ dissolution rates of silicate minerals and associated bacterial communities in the critical zone (Strengbach catchment, France)[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2019, 249: 95-120 DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2019.01.003 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Calvaruso C, Turpault M P, Frey-Klett P. Root-associated bacteria contribute to mineral weathering and to mineral nutrition in trees: A budgeting analysis[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(2): 1258-1266 DOI:10.1128/AEM.72.2.1258-1266.2006 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Story S P. Microbial transport in volcanic tuff Rainier Mesa, Nevada test site[D]. Las Vegas, Nevada, United States: University of Nevada, 1994.

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Purvis G, Sano N, van der Land C, et al. A comparison of the molecular composition of plant and fungal structural biopolymer standards with the organic material in Early Cretaceous Ontong Java Plateau Tuff[J]. Chemical Geology, 2021, 565: 120078 DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120078 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

De Luca D, Caputo P, Perfetto T, et al. Characterisation of environmental biofilms colonising wall paintings of the fornelle cave in the archaeological site of Cales[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(15): 8048 DOI:10.3390/ijerph18158048 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Xi J, Wei M L, Tang B K. Differences in weathering pattern, stress resistance and community structure of culturable rock-weathering bacteria between altered rocks and soils[J]. RSC Advances, 2018, 8(26): 14201-14211 DOI:10.1039/C8RA01268G (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Colin Y, Nicolitch O, Turpault M P, et al. Mineral types and tree species determine the functional and taxonomic structures of forest soil bacterial communities[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2017, 83(5): e02684-e02616 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Herlemann D P, Labrenz M, Jürgens K, et al. Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea[J]. The ISME Journal, 2011, 5(10): 1571-1579 DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.41 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Sun R B, Zhang X X, Guo X S, et al. Bacterial diversity in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization can be more stably maintained with the addition of livestock manure than wheat straw[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2015, 88: 9-18 DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.05.007 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Langille M G I, Zaneveld J, Caporaso, J G, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2013, 31(9): 814-821 DOI:10.1038/nbt.2676 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Douglas G M, Maffei V J, Zaneveld J R, et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2020, 38(6): 685-688 DOI:10.1038/s41587-020-0548-6 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Huang J, Sheng X F, He L Y, et al. Characterization of depth-related changes in bacterial community compositions and functions of a paddy soil profile[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2013, 347(1): 33-42 DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12218 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Santelli C M, Edgcomb V P, Bach W, et al. The diversity and abundance of bacteria inhabiting seafloor lavas positively correlate with rock alteration[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 11(1): 86-98 DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01743.x (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Lepleux C, Turpault M P, Oger P, et al. Correlation of the abundance of betaproteobacteria on mineral surfaces with mineral weathering in forest soils[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(19): 7114-7119 DOI:10.1128/AEM.00996-12 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Chen W, Wang Q, He L Y, et al. Changes in the weathering activity and populations of culturable rock-weathering bacteria from the altered purple siltstone and the adjacent soil[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2016, 33(8): 724-733 DOI:10.1080/01490451.2015.1085469 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Cockell C S, Olsson K, Knowles F, et al. Bacteria in weathered basaltic glass, Iceland[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2009, 26(7): 491-507 DOI:10.1080/01490450903061101 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Wang Q, Ma G Y, He L Y, et al. Characterization of bacterial community inhabiting the surfaces of weathered bricks of Nanjing Ming city walls[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2011, 409(4): 756-762 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.11.001 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Jones R T, Robeson M S, Lauber C L, et al. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses[J]. The ISME Journal, 2009, 3(4): 442-453 DOI:10.1038/ismej.2008.127 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Weijers J W H, Schouten S, van den Donker J C, et al. Environmental controls on bacterial tetraether membrane lipid distribution in soils[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2007, 71(3): 703-713 DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2006.10.003 (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Carson J K, Campbell L, Rooney D, et al. Minerals in soil select distinct bacterial communities in their microhabitats[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2009, 67(3): 381-388 DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00645.x (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Booth I R. Regulation of cytoplasmic pH in bacteria[J]. Microbiological Reviews, 1985, 49(4): 359-378 DOI:10.1128/mr.49.4.359-378.1985 (  0) 0) |

2. School of Life Sciences, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, China;

3. College of Life Science, Bengbu Medical College, Bengbu, Anhui 233030, China

2024, Vol. 56

2024, Vol. 56