2. 南京农业大学生命科学学院, 南京 210095

昆明市东川区是中国泥石流灾害最频繁、最强烈的地区之一,被认为是泥石流灾害的自然博物馆[1]。长期受构造运动和气候因素的影响,该地区岩石遭受了化学和物理双重风化[2]。岩石可以被视为初级生态系统,由于其独特的矿物成分,只有少数具有岩石风化功能的微生物才能在其表面定殖和生存[3]。因此岩石表面微生物的定殖一直是恶劣生境中生命科学研究的主要焦点。微生物群落在岩石风化和土壤形成过程中发挥重要作用[4],能通过氧化还原反应、酸解反应、鳌合反应等作用方式加速岩石的风化[5-9]。

关于不同生态系统中微生物分布、组成及其风化潜能已有大量报道[10-13]。部分研究还特别关注了矿物风化细菌在贫营养的森林生态系统中的作用[14-15]。不同的岩石表面栖息着截然不同的微生物群落[16-17],它们通过生物风化获取岩石中的养分元素来满足自身生长的需求[18-19]。根据先前的研究,岩石表生微生物定殖受岩石基质物理和化学性质的影响,如空隙结构、表面电荷、矿物组分(或岩石种类)和渗透性;表生微生物的定殖也受环境因子的影响,比如气候变化、养分和水分含量等[11]。尽管关于不同岩石表生微生物群落的组成与多样性已有大量报道(包括砂岩、石灰石、白云石、碳酸盐矿物、花岗岩、凝灰岩、玄武岩等)[4],但是尚未有关于泥石流地区不同风化程度岩石表生细菌群落结构、多样性及其驱动因素的相关研究。因此,本研究利用高通量测序技术研究泥石流物源区、流通区岩石表生细菌群落结构与多样性,并通过冗余分析(RDA)探究岩石样品理化性质对岩石表生细菌群落变异的驱动作用。

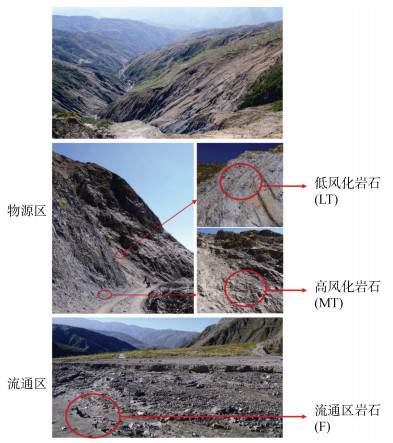

1 材料与方法 1.1 样品采集2014年10月于云南省昆明市东川区蒋家沟山谷变质板岩沉积区(20°14ˊN, 103°08ˊE)采集物源区低风化(LT组)和高风化(MT组)岩石样品以及流通区(F组)岩石样品(图 1)。岩石的风化程度通过肉眼观察进行判断。用95% 工业酒精表面消毒后的铲子收集岩石样品后装入无菌牛皮纸袋中。对于低风化的岩石样品,用表面消毒的锤子敲击岩石获得。每组岩石样品取3份重复。岩石样品收集后过2 mm筛,一部分用干冰保鲜运送回实验室后–80 ℃冻存以便后续提取DNA;另一部分岩石样品风干后常温保存以便后续进行理化性质分析。

|

图 1 采样点照片 Fig. 1 Images of the sampling sites |

称取1 g风干岩石样品,按1∶5 (m/V)的比例加入煮沸后的去离子水(去除水中CO2),摇床150 r/min振荡30 min后用pH计(PHS-3CT,中国上海)测定悬液的pH。采用重铬酸钾外加热法测定有机质含量。分别用0.5 mol/L NaOH和乙酸钠–乙酸(pH 4.0)溶液浸提岩石中的Al和Si,然后用分光光度法测定其含量。对于岩石中有效态Ca、Cu、Fe、K、Mg、Mn和Na含量的测定,则参考Huang等[20]的方法,使用M3试剂[21]浸提后利用电感耦合等离子体光学发射光谱仪(ICP-OES)(Optimal 2100DV,Perkin-Elmer,USA)测定。

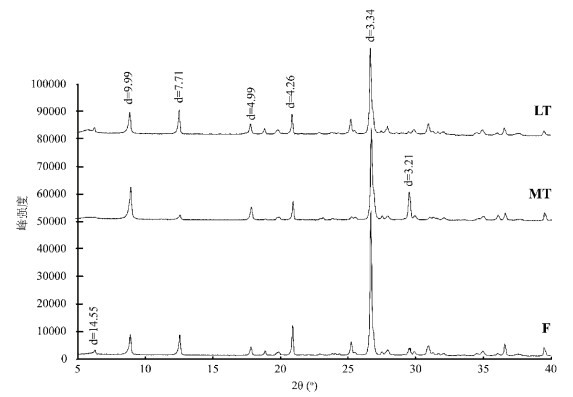

参照Wang等[22]的方法,将岩石样品研磨成粉末后,通过X衍射分析(XRD)检测岩石样品的矿物组成。关于岩石样品的粒径分析则参考Stemmer等[23]的方法通过湿筛和离心法分析岩石样品中不同粒径的质量占比。

1.3 岩石样品DNA提取、PCR扩增与MiSeq高通量测序称取1 g岩石样品利用Fast DNA® Spin kit soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA)试剂盒提取岩石表面总DNA。参考Wang等[24]的方法,利用515F/806R引物[25]对细菌16S rRNA基因V4可变区约300 bp的序列进行PCR扩增;每个引物上都连接了12 bp的独特barcode以区分不同样品。然后,使用Illumina MiSeq PE250平台(Illumina,San Diego,CA)对纯化后的PCR样品进行高通量配对末端测序。获得的序列上传至NCBI数据库,登录号为PRJNA985102。

1.4 数据统计分析利用i-Sanger云数据分析平台(http://www.i-sanger.com)对高通量测序获得的数据进行分析。原始数据质控后,利用UCLST将高质量序列聚类成OTU(相似性不低于97%[26])。利用RDP数据对每个OTU进行鉴定,置信阈值为0.80[27]。为避免不同测序深度对结果分析产生干扰,从每份样本中随机抽取110 000条序列进行后续α和β多样性分析。选择Shannon指数[28]、Chao1指数[29]和Faith系统发育多样性指数(Faith’s PD)[30]为指标比较不同样品间α多样性的差异。采用主坐标分析(PCoA),分别根据计算出的Bray-Curtis距离、未加权的unifrac距离和加权的unifrac距离,评估样本之间微生物群落组成的差异,并采用ANOSIM[31]和ADONIS分析[32]对差异的显著性进行检测。此外,还利用UPGMA法对样品进行聚类分析[33]。利用R语言包进行RDA分析以探究岩石样品理化性质对板岩表生细菌群落变异的驱动作用。通过Spearman相关性分析探究细菌群落α多样性、优势细菌菌门相对丰度之间可能的相关性(SPSS v.21)[34]。利用Tukey-Kramer HSD检验不同处理间差异的显著性。

2 结果与分析 2.1 不同风化程度板岩理化性质如表 1所示,不同样品组间有效态Al、K、Si和Mn含量和有机质(OM)存在显著差异。有效态Al含量由高到低依次是LT组 > MT组 > F组。有效态K含量由高到低依次是MT组 > LT组 > F组。有效态Si、Mn和有机质含量由高到低依次是LT组 > F组 > MT组。MT组和F组的有效态Ca含量没有显著差异,但均显著高于LT组。所有岩石样品均呈碱性(pH 7.79 ~ 8.40)。

|

|

表 1 物源区不同岩石样品的化学性质 Table 1 Chemical properties of different slate rock samples |

结合岩石形貌与XRD衍射分析,本研究所采集的岩石样品均为板岩,不同组板岩样品具有相似的矿物组分,主要包括蒙脱石、高岭石、黑云母和石英(图 2)。值得注意的是,仅在MT组岩石样品中发现了方解石的特征峰(d=3.21)。不同岩石样品的粒径占比如表 2所示,其中砾石的质量占比从高到低依次是LT组 > MT组 > F组,这表明3组板岩样品的风化程度由低到高依次是LT组 < MT组 < F组。

|

图 2 不同岩石样品的矿物组分分析 Fig. 2 Mineralogical compositions of different rock samples |

|

|

表 2 不同岩石样品粒径组成 Table 2 Compositions of particle size fractions of different slate rock samples |

细菌群落16S rRNA基因测序共获得123 369条高质量序列(每份样品11 662 ~ 15 258条优质序列)。这些序列分别归属于29个门,92个纲,134个目和200个科。其中Firmicutes(厚壁菌门,相对丰度占比66%)、Proteobacteria(变形菌门,相对丰度15%)、Actinobacteria(放线菌门,相对丰度11%)为最优势菌门。

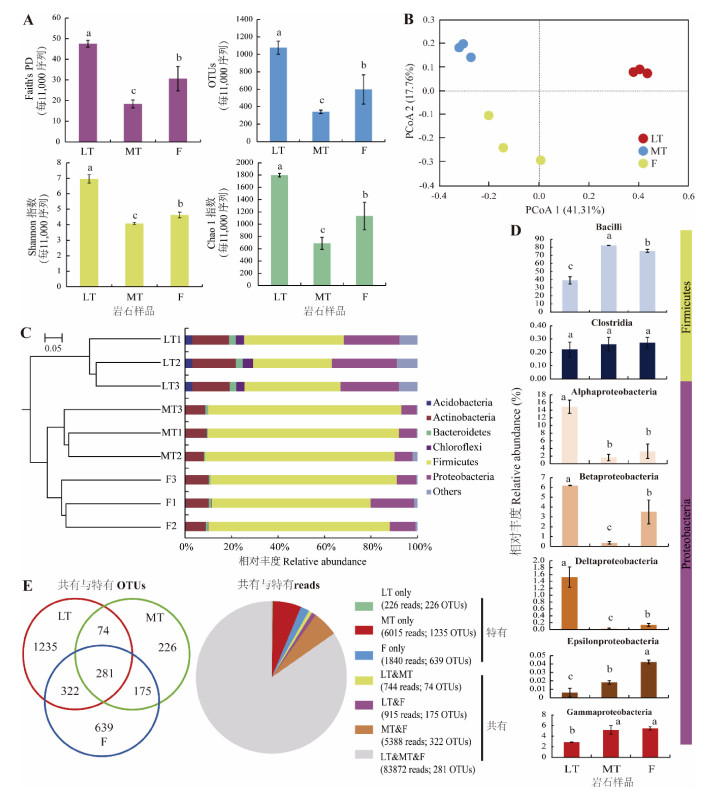

以Faith’s系统发育多样性指数(Faith’s PD)、Shannon指数、Chao1指数和每个样品包括的独特OTU数目作为指标比较不同组岩石样品表生细菌群落α多样性,结果如图 3A所示,不同组岩石样品间α多样性存在显著差异。总体上,LT组岩石样品细菌群落α多样性指数均显著高于MT组和F组岩石样品,表明低风化的板岩样品表生细菌群落α多样性更高。

|

(A:α多样性指数;B:群落结构PCoA聚类分析;C:UPGMA聚类分析及优势菌门相对丰度;D:优势菌纲相对丰度;E:OTU分布,左边为特有和共有OTU的分布,右边为对应序列数。图D中,柱图上方不同小写字母表示不同样品间差异显著(P < 0.05)) 图 3 不同岩石样品表生细菌群落α多样性和群落结构比较 Fig. 3 Comparison of α diversity indices and bacterial community compositions inhabiting different rock surfaces |

基于Bray-Curtis相似距离计算的PCoA分析和UPGMA聚类分析被用来比较OTU水平上不同岩石样品表生细菌群落结构的差异,结果如图 3B、3C所示,所有样品聚成独立的3组,其中MT组与F组岩石样品细菌群落结构更相似,与LT组岩石样品细菌群落存在显著差异。这一结论也进一步为ADONIS和ANOSIM分析所证实(表 3)。

|

|

表 3 LT、MT和F组岩石样品表生细菌群落相似性比较 Table 3 Similarity comparison of bacterial community compositions among LT, MT and F groups |

在门水平上,LT组岩石样品Actinobacteria和Proteobacteria菌门的相对丰度最高,其次是F组,MT组岩石样品中其相对丰度最低。不同岩石样品表生细菌菌群中Chloroflexi(绿弯菌门)和Firmicutes菌门的相对丰度由高到低分别为MT组 > F组 > LT组。不同采样点岩石表生细菌纲水平上的优势类群的相对丰度也有所不同(图 3D)。对于相对丰度最高的Firmicutes菌门,MT组中Bacilli(杆菌纲)的相对丰度最高,其次是F组,然后是LT组。

在属水平上,分别从LT组、MT组和F组岩石样品鉴定到190、125和172个菌属。本研究将占所有序列相对丰度0.25% 以上的菌属定义为优势菌属。如表 4所示,MT组和F组岩石样品中Lactococcus(乳球菌属)、Streptococcus(链球菌属)、Lactobacillus(乳酸杆菌属)、Leuconostoc(明串珠菌属)、Bacillus(芽孢杆菌属)、Solibacillus(森林土源芽孢杆菌属)、Lysinibacillus (赖氨酸芽孢杆菌属)、Exiguobacterium(微小杆菌属)、Brochothrix(环丝菌属)、Caulobacter(柄杆菌属)和Pseudomonas(假单胞菌属)的相对丰度显著高于LT组岩石样品。而LT组岩石样品中隶属于Actinobacteria菌门的Modestobacter (贫养杆菌属)、隶属于Bacteroidetes菌门的Flavisolibacter(黄色土源菌属)、隶属于Planctomycetes菌门的Gemmata(出芽菌属)、Alphaproteobacteria菌纲的Sphingomonas(鞘鞍醇单胞菌属)和Methylobacterium(甲基杆菌属)以及与氨氧化相关的Nitrospira(硝化螺旋菌属)显著高于MT组和F组岩石样品。而Rhodobacter(红细菌属)、Hydrogenophaga (氢噬胞菌属)和Limnobacter(林杆菌属)仅在F组样品中检测到。

|

|

表 4 优势菌属在不同岩石样品间的分布 Table 4 Distributions of abundant genus among different rock samples |

在OTU水平上,3个不同采样位点的板岩表生细菌共检测到3 114个OTU,其中281个OTU是3组岩石样品共有的OTU,占所有序列数的9.5%,表明这些共有OTU大多是丰富物种。而每组岩石特有的OTU大多为丰富度较低的物种(图 3E)。此外,LT组特有OTU数量(占3 114个OTU的41.8%)大于MT组(7.6%)和F组(2.5%)。

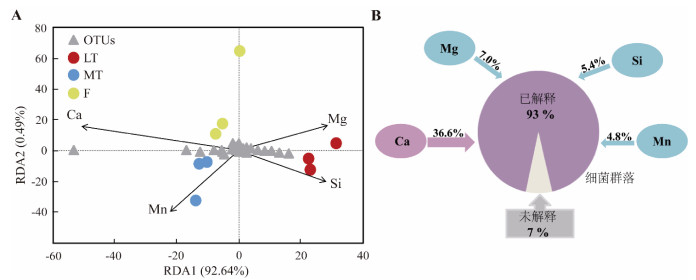

2.4 岩石理化性质对板岩表生细菌群落的影响与RDA模型显著相关(P < 0.05)的岩石理化因子(包括板岩中有效态Ca、Mg、Si和Mn的含量)被挑选出来研究其对板岩细菌群落组成的影响。如图 4所示,以上4种理化因子解释了93% 的板岩表生细菌群落变异(图 4A),而有效态Ca含量是板岩表生细菌群落变异的主要贡献者,解释了36.6% 的变异度(图 4B)。

|

图 4 不同岩石样品表生细菌群落结构冗余分析(RDA)(A)及岩石样品中有效态Ca、Mg、Si和Mn含量对岩石表生细菌群落变异的解释度(B) Fig. 4 Redundancy analysis (RDA) of bacterial communities inhabiting slate rock sample surface, which depicts correlation between bacterial communities and rock properties (A) and variance percentages explained by studied rock properties (B) |

表生细菌群落α多样性指数与岩石样品有效态Ca和Mg含量呈显著负相关,与有效态Si和Mn含量呈显著正相关(表 5)。此外,表生细菌群落α多样性指数与有机质含量呈正相关(r=0.80 ~ 0.91,P < 0.01),与pH呈负相关(r= –0.93 ~ –0.91,P < 0.05)。而优势菌门(除了Firmicutes)的相对丰度均与有效态Si和Mn含量呈显著正相关,而与有效态Ca含量呈显著负相关。

|

|

表 5 RDA模型筛选的岩石理化性质指标与表生细菌群落α多样性指数及不同菌门相对丰度之间的相关性 Table 5 Spearman's correlations among α-diversity indexes, relative abundances of bacterial phyla with rock properties selected with RDA model |

不同生态系统中存在着不同的微生物群落[35-36]。Lepleux等[12]发现磷灰石表生细菌的优势菌群主要为Proteobacteria(相对丰度为50% ~ 73%)、Bacteroidetes (7% ~ 37%)和Acidobacteria(1% ~ 16%)。钾质粗面岩表生细菌的优势菌群为Actinobacteria (22% ~ 28%)、Chloroflexi (16% ~ 23%)和Firmicutes (7% ~ 20%)[37]。玄武岩表生细菌中最优势的菌群为Actinobacteria(相对丰度 > 80%),而Proteobacteria占比 < 2.3%;Cynobacteria (蓝细菌门)则为石灰石和灰华石表生细菌群落中的优势种群,相对丰度分别 > 12%和 > 22%[38-42]。本研究发现,板岩表生细菌的优势种群分别为Firmicutes(相对丰度占比34% ~ 83%)、Proteobacteria(7% ~ 28%)和Actinobacteria(8% ~ 19%) (图 3),与其他岩石表生细菌群落明显不同。本研究中,Firmicutes是板岩表面相对丰度最高的菌门,其在土壤、水体和厌氧发酵过程中普遍存在,在有机质的分解和周转中起重要作用[43-44]。Firmicutes菌门的很多菌株可以产生芽孢,能抵御脱水和极端环境。本研究中,Bacillus属是隶属于Firmicutes菌门的板岩表面最优势属。Bacillus属细菌在各种岩石表面和土壤中均能被检测到[20, 38, 40, 45],这可能是因为它们在抑制病原菌、促进植物生长和风化岩石中发挥着重要作用[43, 46]。基于对常见石灰岩–泥岩蚀变岩芯中细菌群落的调查,Lazar等[39]认为芽孢杆菌起源于森林土壤,最有可能以岩石基质中不稳定的有机物输入为食。

岩石风化过程中,不同矿物组分会影响岩石中Ca、Mg、P、K、Si和Al等元素的生物可利用性,因此风化引起的营养阳离子含量的变化会对岩石表生微生物群落的分类和功能多样性产生显著影响[37, 42, 45, 47],尤其岩石养分元素含量会吸引特定种群微生物在岩石表面优先定殖[48]。Wang等[37]发现有效态P含量是钾质粗面岩表生细菌群落最重要的驱动因子,解释了70% 的群落结构变异。含盐量、Ca含量以及含水量被发现是影响盐碱土表生微生物群落的重要环境因子[42]。本研究发现,板岩中有效态Ca含量是板岩表生细菌群落结构变化的主要驱动因素,解释了约37% 的群落结构变异(图 4)。不同种类岩石(矿物)表生微生物群落结构驱动因子的差异,也印证了岩石表生微生物定殖受岩石基质物理和化学性质的影响这一观点。

作为生物体的必需营养元素,Ca参与了许多细菌生长代谢过程,包括热休克、趋化性、分化及细胞分裂等[42]。Sridevi等[49]发现,Ca的添加显著改变了落叶次生林中土壤细菌群落的组成,并影响了数百种细菌类群的相对丰度。Groffman等[50]发现,在北部硬木森林中,Ca的添加导致微生物生物量氮降低。而Kalwasińska等[42]发现,盐碱土中微生物群落OTU的数量与Ca含量呈正相关。以上研究结果的不一致可能是细菌群落所占据的独特微生境造成的。本研究发现,F和MT组板岩样品的Ca含量显著高于低风化LT组板岩样品(表 1);且板岩中有效态Ca含量与Firmicutes的相对丰度呈正相关,与板岩表生细菌群落α多样性指数呈负相关。这可能与岩石样品中有机质含量有关,如表 1所示,LT组板岩样品中有机质含量显著高于MT和F组板岩样品。Kirtzel等[51]发现,当暴露在氧气中时,黑板岩的风化会导致有机质的降解和有机化合物的释放。在本研究中也发现了类似的现象,风化程度较低的LT组板岩样品中有机质含量明显高于风化程度较高的MT和F组板岩;更高的有机质含量能为微生物提供更丰富的营养,所以LT组板岩样品表生细菌群落生物多样性更丰富。而高风化板岩样品中有机质含量的下降可能与Firmicutes相对丰度显著提高相关,因为有研究发现Firmicutes能加速有机质的分解和周转[43-45]。

4 结论本研究首次报道了泥石流源区岩石表生微生物群落结构与生物多样性。研究发现,东川泥石流地区的岩石主要为板岩,板岩风化程度越低其表生细菌群落α多样性指数越高,且α多样性指数与岩石中有机质含量呈显著正相关。板岩表生细菌优势菌门为Firmicutes(厚壁菌门,相对丰度66%)、Proteobacteria (变形菌门,相对丰度15%)和Actinobacteria(放线菌门,相对丰度11%)。低风化物源区岩石样品、高风化物源区岩石样品以及流通区岩石样品表生细菌群落显著不同,而岩石中有效态Ca含量是板岩表生细菌群落结构最主要的驱动因子。

| [1] |

Ding M T, Wei F Q, Hu K H. Property insurance against debris-flow disasters based on risk assessment and the principal–agent theory[J]. Natural Hazards, 2012, 60(3): 801-817 DOI:10.1007/s11069-011-9897-2 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Che V B, Fontijn K, Ernst G G J, et al. Evaluating the degree of weathering in landslide-prone soils in the humid tropics: The case of Limbe, SW Cameroon[J]. Geoderma, 2012, 170: 378-389 DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.10.013 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Uroz S, Calvaruso C, Turpault M P, et al. Mineral weathering by bacteria: ecology, actors and mechanisms[J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2009, 17: 378-387 DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.004 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Esposito A, Ciccazzo S, Borruso L, et al. A three-scale analysis of bacterial communities involved in rocks colonization and soil formation in high mountain environments[J]. Current Microbiology, 2013, 67(4): 472-479 DOI:10.1007/s00284-013-0391-9 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Santelli C M, Welch S A, Westrich H R, et al. The effect of Fe-oxidizing bacteria on Fe-silicate mineral dissolution[J]. Chemical Geology, 2001, 180(1/2/3/4): 99-115 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Benzerara K, Barakat M, Menguy N, et al. Experimental colonization and alteration of orthopyroxene by the pleomorphic bacteria Ramlibacter tataouinensis[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2004, 21(5): 341-349 DOI:10.1080/01490450490462039 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

van Thienen P, Benzerara K, Breuer D, et al. Water, life, and planetary geodynamical evolution[J]. Space Science Reviews, 2007, 129(1): 167-203 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Balland C, Poszwa A, Leyval C, et al. Dissolution rates of phyllosilicates as a function of bacterial metabolic diversity[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2010, 74(19): 5478-5493 DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2010.06.022 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Ferret C, Sterckeman T, Cornu J Y, et al. Siderophore- promoted dissolution of smectite by fluorescent Pseudomonas[J]. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2014, 6(5): 459-467 DOI:10.1111/1758-2229.12146 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Hutchens E, Valsami-Jones E, McEldowney S, et al. The role of heterotrophic bacteria in feldspar dissolution–an experimental approach[J]. Mineralogical Magazine, 2003, 67(6): 1157-1170 DOI:10.1180/0026461036760155 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Calvaruso C, Turpault M P, Frey-Klett P. Root-associated bacteria contribute to mineral weathering and to mineral nutrition in trees: A budgeting analysis[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(2): 1258-1266 DOI:10.1128/AEM.72.2.1258-1266.2006 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Lepleux C, Turpault M P, Oger P, et al. Correlation of the abundance of betaproteobacteria on mineral surfaces with mineral weathering in forest soils[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(19): 7114-7119 DOI:10.1128/AEM.00996-12 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Lapanje A, Wimmersberger C, Furrer G, et al. Pattern of elemental release during the granite dissolution can be changed by aerobic heterotrophic bacterial strains isolated from damma glacier (central Alps) deglaciated granite sand[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(4): 865-882 DOI:10.1007/s00248-011-9976-7 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Uroz S, Turpault M P, Van Scholl L, et al. Long term impact of mineral amendment on the distribution of the mineral weathering associated bacterial communities from the beech Scleroderma citrinum ectomycorrhizosphere[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2011, 43(11): 2275-2282 DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.07.010 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Colin Y, Nicolitch O, Turpault M P, et al. Mineral types and tree species determine the functional and taxonomic structures of forest soil bacterial communities[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2017, 83(5): e02684-e02616 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Matlakowska R, Sklodowska A. The culturable bacteria isolated from organic-rich black shale potentially useful in biometallurgical procedures[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2009, 107(3): 858-866 DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04261.x (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Olsson-Francis K, Simpson A E, Wolff-Boenisch D, et al. The effect of rock composition on cyanobacterial weathering of crystalline basalt and rhyolite[J]. Geobiology, 2012, 10(5): 434-444 DOI:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2012.00333.x (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Matlakowska R, Skłodowska A, Nejbert K. Bioweathering of Kupferschiefer black shale (Fore-Sudetic Monocline, SW Poland) by indigenous bacteria: Implication for dissolution and precipitation of minerals in deep underground mine[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2012, 81(1): 99-110 DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01326.x (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Zhao F, Qiu G, Huang Z, et al. Characterization of Rhizobium sp. Q32 isolated from weathered rocks and its role in silicate mineral weathering[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2013, 30(7): 616-622 DOI:10.1080/01490451.2012.746406 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Huang J, Sheng X F, Xi J, et al. Depth-related changes in community structure of culturable mineral weathering bacteria and in weathering patterns caused by them along two contrasting soil profiles[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(1): 29-42 DOI:10.1128/AEM.02335-13 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Mehlich A. Mehlich 3 soil test extractant: A modification of Mehlich 2 extractant[J]. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 1984, 15(12): 1409-1416 DOI:10.1080/00103628409367568 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Wang Q, Cheng C, He L Y, et al. Characterization of depth-related changes in bacterial communities involved in mineral weathering along a mineral-rich soil profile[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2014, 31(5): 431-444 DOI:10.1080/01490451.2013.848248 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Stemmer M, Gerzabek M H, Kandeler E. Organic matter and enzyme activity in particle-size fractions of soils obtained after low-energy sonication[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1998, 30(1): 9-17 DOI:10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00093-X (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Wang Q, Li Z Z, Li X W, et al. Interactive effects of ozone exposure and nitrogen addition on the rhizosphere bacterial community of poplar saplings[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 754: 142134 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142134 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Hugerth L W, Wefer H A, Lundin S, et al. DegePrime, a program for degenerate primer design for broad-taxonomic- range PCR in microbial ecology studies[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(16): 5116-5123 DOI:10.1128/AEM.01403-14 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Edgar R C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST[J]. Bioinformatics, 2010, 26(19): 2460-2461 DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Cole J R, Chai B, Farris R J, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): Sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2005, 33(Database issue): D294-D296 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Izsák J. Parameter dependence of correlation between the Shannon index and members of parametric diversity index family[J]. Ecological Indicators, 2007, 7(1): 181-194 DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2005.12.001 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Faulkner J R, Magee A F, Shapiro B, et al. Horseshoe- based Bayesian nonparametric estimation of effective population size trajectories[J]. Biometrics, 2020, 76(3): 677-690 DOI:10.1111/biom.13276 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Faith D P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity[J]. Biological Conservation, 1992, 61(1): 0006320792912013 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Ramírez C, Romero J. The microbiome of Seriola lalandi of wild and aquaculture origin reveals differences in composition and potential function[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 1844 DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01844 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Pärnänen K, Karkman A, Hultman J, et al. Maternal gut and breast milk microbiota affect infant gut antibiotic resistome and mobile genetic elements[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 3891 DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-06393-w (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Caporaso J G, Bittinger K, Bushman F D, et al. PyNAST: A flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment[J]. Bioinformatics, 2010, 26(2): 266-267 DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Hauke J, Kossowski T. Comparison of values of pearson's and spearman's correlation coefficients on the same sets of data[J]. QUAGEO, 2011, 30(2): 87-93 DOI:10.2478/v10117-011-0021-1 (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Kelly L C, Cockell C S, Piceno Y M, et al. Bacterial diversity of weathered terrestrial Icelandic volcanic glasses[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2010, 60(4): 740-752 DOI:10.1007/s00248-010-9684-8 (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Olsson-Francis K, Pearson V K, Schofield P F, et al. A study of the microbial community at the interface between granite bedrock and soil using a culture-independent and culture-dependent approach[J]. Advances in Microbiology, 2016, 6(3): 233-245 DOI:10.4236/aim.2016.63023 (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Wang Q, Cheng C, Agathokleous E, et al. Enhanced diversity and rock-weathering potential of bacterial communities inhabiting potash trachyte surface beneath mosses and lichens - A case study in Nanjing, China[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 785: 147357 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147357 (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Choe Y H, Kim M, Woo J, et al. Comparing rock- inhabiting microbial communities in different rock types from a high Arctic polar desert[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2018, 94(6) DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiy070 (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Lazar C S, Lehmann R, Stoll W, et al. The endolithic bacterial diversity of shallow bedrock ecosystems[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 679: 35-44 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.281 (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Lee J, Cho J, Cho Y J, et al. The latitudinal gradient in rock-inhabiting bacterial community compositions in Victoria Land, Antarctica[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 657: 731-738 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.073 (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Tang Y, Lian B, Dong H L, et al. Endolithic bacterial communities in dolomite and limestone rocks from the Nanjiang Canyon in Guizhou karst area (China)[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2012, 29(3): 213-225 DOI:10.1080/01490451.2011.558560 (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Kalwasińska A, Deja-Sikora E, Szabó A, et al. Salino- alkaline lime of anthropogenic origin a reservoir of diverse microbial communities[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 655: 842-854 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.246 (  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Chen S, Cheng H C, Wyckoff K N, et al. Linkages of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes populations to methanogenic process performance[J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 2016, 43(6): 771-781 (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Seong C N, Kang J W, Lee J H, et al. Taxonomic hierarchy of the Phylum Firmicutes and novel Firmicutes species originated from various environments in Korea[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2018, 56(1): 1-10 DOI:10.1007/s12275-018-7318-x (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Tang J, Tang X X, Qin Y M, et al. Karst rocky desertification progress: Soil calcium as a possible driving force[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 649: 1250-1259 DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.242 (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Wang Q, Xie Q D, He L Y, et al. The abundance and mineral-weathering effectiveness of Bacillus strains in the altered rocks and the soil[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2018, 58(9): 770-781 DOI:10.1002/jobm.201800141 (  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Gleeson D B, Kennedy N M, Clipson N, et al. Characterization of bacterial community structure on a weathered pegmatitic granite[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2006, 51(4): 526-534 DOI:10.1007/s00248-006-9052-x (  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Carson J K, Campbell L, Rooney D, et al. Minerals in soil select distinct bacterial communities in their microhabitats[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2009, 67(3): 381-388 DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00645.x (  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Sridevi G, Minocha R, Turlapati S A, et al. Soil bacterial communities of a calcium-supplemented and a reference watershed at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest (HBEF), New Hampshire, USA[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2012, 79(3): 728-740 DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01258.x (  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Groffman P M, Fisk M C, Driscoll C T, et al. Calcium additions and microbial nitrogen cycle processes in a northern hardwood forest[J]. Ecosystems, 2006, 9(8): 1289-1305 DOI:10.1007/s10021-006-0177-z (  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Kirtzel J, Ueberschaar N, Deckert-Gaudig T, et al. Organic acids, siderophores, enzymes and mechanical pressure for black slate bioweathering with the basidiomycete Schizophyllum commune[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2020, 22(4): 1535-1546 DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.14749 (  0) 0) |

2. College of Life Sciences, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, China

2024, Vol. 56

2024, Vol. 56