2. 江苏省沿江地区农业科学院, 江苏南通 226541

土壤导热率是土壤热状况的内在因素,影响土壤热量传递、微生物活动、种子萌发和根系生长等一系列活动[1-3]。国内外研究已明确土壤导热率随土壤质地、含水率、孔隙度、有机质含量而发生剧烈变化[2, 4-6],其核心在于土壤多孔介质中固、液、气三相比例和组分的改变[6]。

土壤团聚体作为衡量土壤结构优劣的重要指标,其粒径大小、数量、分布以及由此产生的孔隙结构能够影响土壤水、气的运动和有机质的积累,进而改变土壤热量的传递[7-11]。Usowicz等[12]通过室内模拟试验,发现在相同含水率和容重的条件下,土壤导热率随团聚体粒径的降低而增加。Ju等[13]通过室内模拟试验,发现在中等含水率下,团聚体土壤(< 2 mm)导热率显著低于非团聚体土壤(< 0.1 mm)。邸佳颖等[14]通过比对原状土与干扰土的导热率,发现原状土的导热率显著高于干扰土。然而,目前关于团聚体与土壤导热率之间关系的研究,侧重于单一团聚体粒径或者团聚体结构的影响,缺乏团聚体粒径分布对土壤导热率影响的研究。因此,本研究以长期定位试验土壤为研究对象,采用室内模拟试验的研究方法,利用热脉冲技术测定不同团聚体粒径分布下土壤导热率的变化特征,以探究团聚体粒径分布与土壤导热率之间的关系,为土壤导热率影响因素的研究和土壤抗热性管理措施的制定提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 供试土壤供试土壤采自江苏省沿江地区农业科学院长期定位试验田(120°37'E,32°07'N)。长期定位试验始于1979年,种植制度为大麦–棉花–小麦–水稻–蚕豆–玉米3年6熟制,土壤类型为灰潮土,质地为粉(砂)质黏壤土。供试土壤为2021年玉米收获后的不施肥(CK)、单施有机肥(M)、有机无机肥配施(MNPK)3个处理土壤,采集深度为0 ~ 15 cm土层,其理化性状见表 1。

|

|

表 1 供试土壤的基本理化特性 Table 1 Tested soil basic properties under 42 years of fertilization |

土壤样品室内风干,在风干过程中,不间断地将土壤颗粒沿裂缝轻轻掰分至小于2 mm,同时剔除残留的根系和秸秆。随后,参考Tian等[10]湿筛法分别对CK、M、MNPK土壤进行团聚体分级,分离出0.25 ~ 2、0.053 ~ 0.25、< 0.053 mm三种粒径大小的团聚体颗粒。按照大(0.25 ~ 2 mm)、中(0.053 ~ 0.25 mm)、小(< 0.053 mm)团聚体质量占比(%)100-0-0(S100-0-0)、0-100-0(S0-100-0)、0-0-100(S0-0-100)、50-25-25(S50-25-25)、25-50-25(S25-50-25)、25-25-50(S25-25-50)6个配比(表 2),等容重(平均1.36 g/cm3,变异在± 3% 内)填充土柱(高5 cm、直径5 cm),每个配比设置3个重复,共54个土柱。采用注射器将去离子水缓慢注入土柱中,设置不同体积含水量处理(0、0.10、0.20、0.25、0.30 cm3/cm3,对应的水分饱和度(Sr,含水率/孔隙度)分别为0、0.14、0.20、0.27、0.34、0.41),保鲜膜封口后,在40 ℃恒温培养箱中放置24 h,再在室温下平衡24 h后,测定土壤导热率,每个土柱测定4次,取平均值。

|

|

表 2 各处理的土壤团聚体配比及平均重量直径 Table 2 Soil aggregate proportions and mean weight diameters under different treatments |

采用METER公司生产的Tempos热特征分析仪联合SH-3双针传感器测定土壤导热率[5, 15]。该设备基于脉冲无限线性热源理论计算得到导热率,较其他测试设备和方法能够缩短加热和测量时间,最大限度地减少因探针加热造成的水分迁移,增加测量值的准确性。采用重铬酸钾–硫酸溶液氧化法测定配比后的土壤有机碳含量,按1.724转化系数计算有机质(SOM)含量。

1.4 数据处理与分析为了更好地反映不同团聚体粒径分布下土壤导热率与含水率之间的关系,本研究基于Johansen[16]建立的导热率λ与Ke(Kersten数)之间的关系,结合Lu等[17]与苏李君等[18]提出的Ke与水分饱和度指数函数表达式,对土壤导热率与水分饱和度(Sr)进行模型拟合。方程如下:

| $ \lambda=\left(\lambda_{\mathrm{s}}-\lambda_{\mathrm{d}}\right) \times \mathrm{Ke}+\lambda_{\mathrm{d}} $ | (1) |

式中:λs为饱和土壤导热率(土壤处于最大持水量时的导热率,W/(m·K));λd为干土导热率(W/(m·K))。

| $ \mathrm{Ke}=\exp \left(m\left(1-S_r^{m-1.33}\right)\right) $ | (2) |

式中:m为拟合参数,本研究供试土壤砂粒平均含量在40% 左右,因此取值0.92[18];1.33为土壤形状参数。

另外,本文采用SPSS 22.0软件对数据进行方差分析及LSD法差异检验显著性(P < 0.05),采用Origin 2018软件进行模型拟合和回归分析。

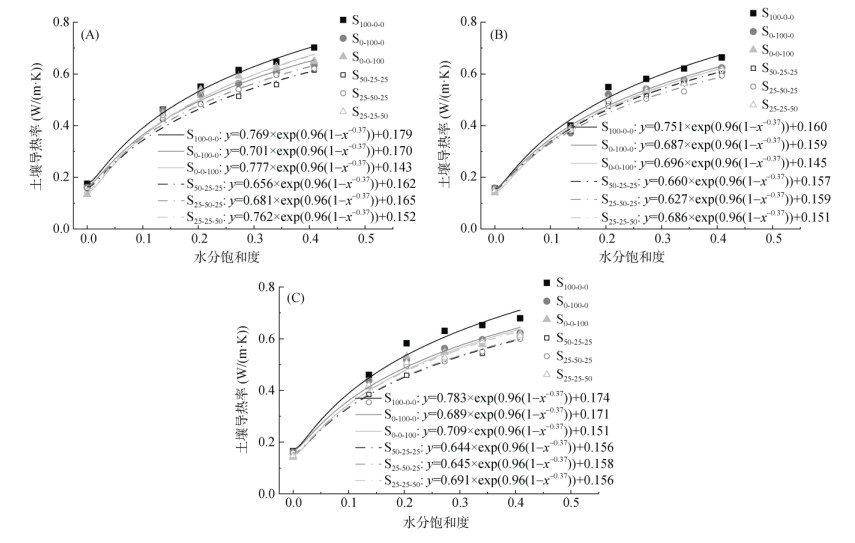

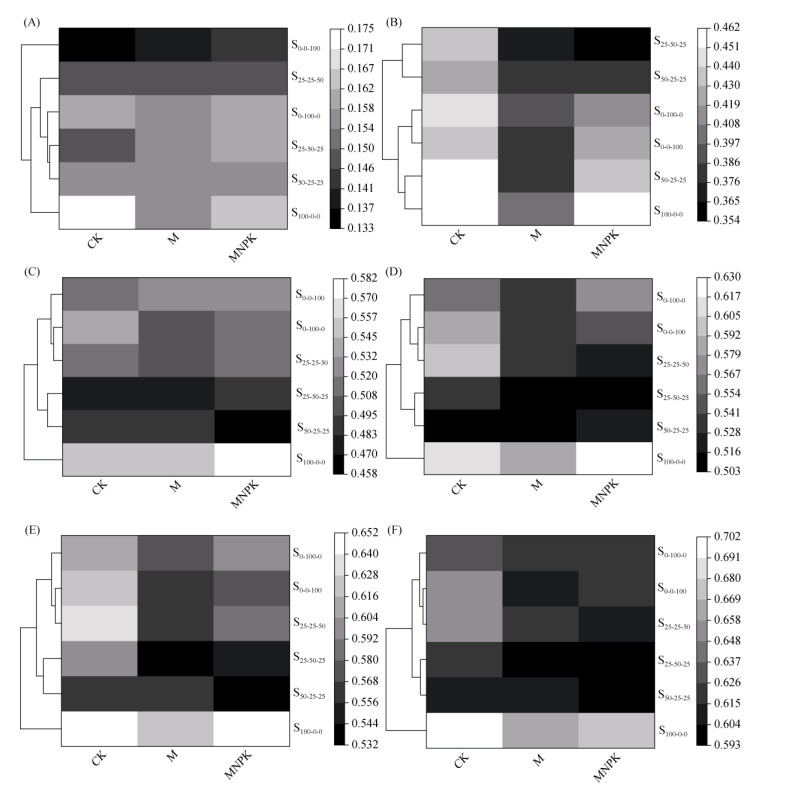

2 结果与分析 2.1 土壤导热率变化特征如图 1所示,各团聚体配比处理土壤导热率随水分饱和度的增加而增加。在相同水分饱和度下,土壤导热率受团聚体组成的影响差异显著(图 1,表 3)。对于干土,含大、中团聚体比例高的土壤导热率显著高于含小团聚体比例高的土壤,具体表现为S100-0-0 > S0-100-0 > S25-50-25 > S50-25-25 > S25-25-50 > S0-0-100,3种施肥土壤的变化趋势一致(图 1和图 2A,表 3)。当水分饱和度从0增加到0.41时,S100-0-0、S50-25-25、S0-100-0、S25-50-25处理的土壤导热率分别提高了3.01倍~ 3.17倍、2.89倍~ 2.94倍、2.84倍~ 2.96倍、2.78倍~ 2.89倍,低于S0-0-100和S25-25-50处理的3.35倍~ 3.86倍和3.23倍~ 3.45倍。聚类分析结果表明,在相同土壤水分饱和度条件下,各处理的非饱和土壤导热率(土壤孔隙空间未被水完全充满(即同时存在液态水、空气和其他气相)时的土壤导热率)变化趋势均表现为S100-0-0 > S0-100-0 > S25-25-50、S0-0-100 > S50-25-25、S25-50-25(图 2B~2F)。

|

(图A、B和C分别为CK、M和MNPK土壤) 图 1 各处理土壤导热率与水分饱和度之间的关系 Fig. 1 Relationship between soil conductivity and soil water saturability under different treatments |

|

|

表 3 各处理土壤导热率的方差分析 Table 3 Variance analysis of soil thermal conductivities under different treatments |

|

(图A ~ F土壤水分饱和度分别为0、0.14、0.20、0.27、0.34和0.41) 图 2 不同水分饱和度下土壤导热率的聚类热图 Fig. 2 Clustered heatmap of soil thermal conductivities under different soil water saturabilities |

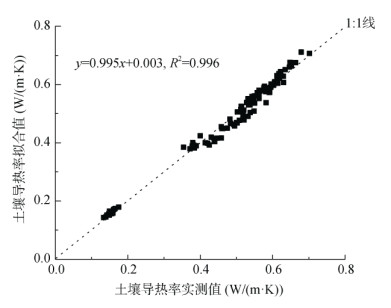

根据Lu等[17]提出的土壤导热率经验模型进行拟合,发现土壤导热率实测值和拟合值的离散点均匀分布在1∶1线附近,R2值达0.99(图 3),说明该模型具有很高的精准度。

|

图 3 土壤导热率实测值和拟合值比较 Fig. 3 Comparison of measured and fitted soil thermal conductivities |

通过模型拟合方程计算饱和土壤导热率拟合值和导热率变化值(λs – λd)(表 4),结果表明,在所有处理中,S100-0-0处理的饱和土壤导热率拟合值最高。较S100-0-0处理,S0-100-0、S0-0-100、S50-25-25、S25-50-25、S25-25-50处理的饱和土壤导热率拟合值分别降低了7.14% ~ 10.14%、2.95% ~ 10.14%、10.31% ~ 16.41%、10.76% ~ 16.09%、3.39% ~ 11.49%。在3种施肥土壤中,S100-0-0(0.75 ~ 0.78 W/(m·K))、S0-0-100(0.67 ~ 0.78 W/(m·K))和S25-25-50(0.69 ~ 0.76 W/(m·K))的导热率变化值均低于S50-25-25(0.64 ~ 0.66 W/(m·K))和S25-50-25(0.63 ~ 0.68 W/(m·K))(表 4)。

|

|

表 4 各处理干土和饱和土壤导热率的拟合值以及导热率变化值(W/(m·K)) Table 4 Fitted dry and saturated soil thermal conductivities and change of thermal conductivities under different treatments |

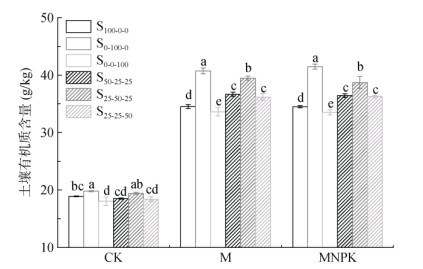

在不同团聚体组成下,CK、M和MNPK土壤有机质含量的变化范围分别为18.03 ~ 19.79、33.62 ~ 40.74和33.03 ~ 41.46 g/kg(图 4)。在所有处理中,S0-100-0处理的土壤有机质含量最高,S0-0-100处理最低,具体表现为S0-100-0 > S25-50-25 > S50-25-25、S50-25-25 > S100-0-0 > S0-0-100,3种施肥土壤的变化趋势表现一致。

|

(柱图上方不同小写字母表示同一土壤下不同团聚体配比间差异在P < 0.05水平显著) 图 4 各处理土壤有机质含量变化特征 Fig. 4 Soil organic matter contents under different soil aggregate proportions |

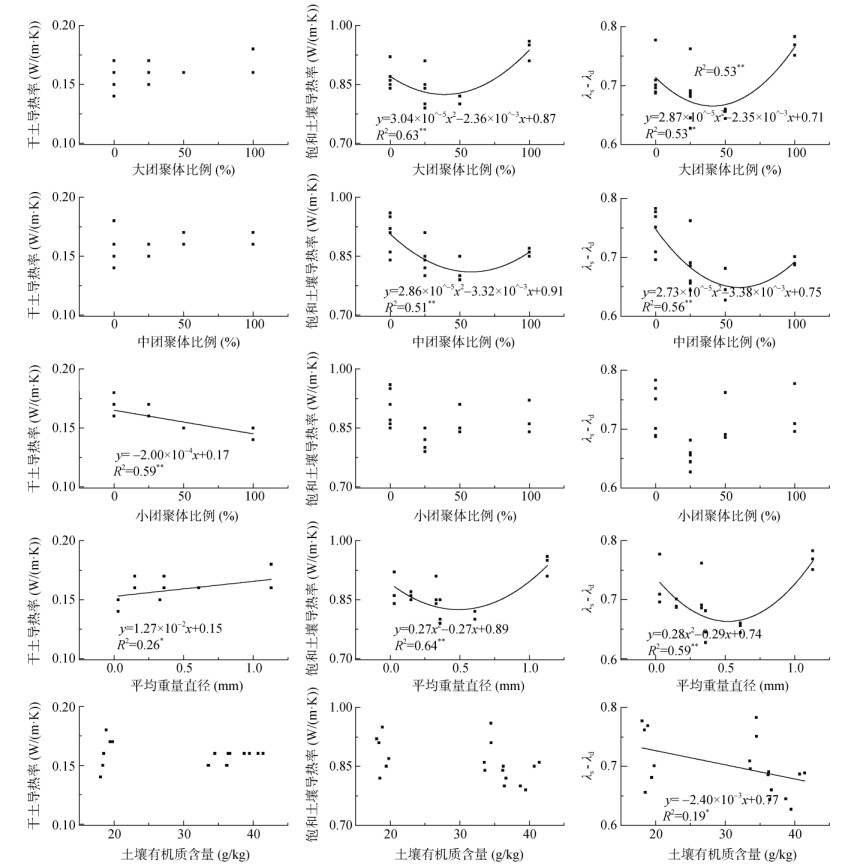

如图 5所示,干土导热率与小团聚体比例(R2=0.59**)和平均重量直径(R2=0.26*)呈显著线性负相关关系。饱和土壤导热率与大团聚体比例(R2=0.63**)、中团聚体比例(R2=0.51**)和平均重量直径(R2=0.64**)之间的关系符合一元二次方程。土壤导热率变化值与大团聚体比例(R2=0.53**)、中团聚体比例(R2=0.56**)和平均重量直径(R2=0.59**)存在一元二次线性关系,与土壤有机质含量呈显著线性负相关关系(R2=0.19*)。

|

图 5 干土导热率、饱和土壤导热率拟合值以及土壤导热率变化值与大、中、小团聚体比例及平均重量直径和有机质含量的回归分析 Fig. 5 Regression analysises of fitted dry soil thermal conductivity, water saturated soil thermal conductivity, and change value of soil thermal conductivity with the proportions of large, medium, and small aggregates, mean mass diameter and organic matter content |

本研究中,不同团聚体粒径分布下土壤导热率与水分饱和度之间的关系符合Lu等[17]提出的指数函数表达式,即随水分饱和度的增加,土壤导热率呈先快后慢的变化规律,这与已有研究结果一致[18-21]。土壤三相中,导热率大小为固相(2.90 W/(m·K)) > 液相(0.57 W/(m·K)) > 气相(0.0025 W/(m·K)),在低含水率阶段,土壤通过固/固、气/固和气/液/固进行热量的传递[6]。随着含水率的增加,附着在土壤固体颗粒表面的水膜逐渐增厚,形成“水桥”,固体颗粒间的连接点和接触面积增加,热量传递途径由气/固或气/液/固向液/固转变,造成导热率快速增加[14, 19-20]。Radhakrishna等[21]将土壤导热率随含水率小幅度降低而非线性增加时的含水率,称为“临界含水率”,其与黏土矿物、颗粒形状和粒径分布有关[6, 22]。Zhang等[22]发现当含水率增加到临界含水率后,固体颗粒间的有效接触面积不再随含水率的增加而增加。因此,在高含水率阶段,土壤趋于饱和,热量通过液/固、固/固接触进行传递[6],导热率增加减缓。

本研究发现,在等干密度条件下,含大、中团聚体比例高的干土导热率高于含小团聚体比例高的土壤,这与邸佳颖等[14]研究结果一致。在等干密度条件下,含大团聚体比例高的土壤,固体颗粒间的挤压强度较大,固体颗粒间的排列相对紧密,彼此间的接触点增加、接触角缩小、有效接触面积增加,热阻降低,有利于热量通过固/固接触传递[14, 19]。反之,固体颗粒间的排列相对分散,气/固途径传递增加,热传递效率下降。然而,Usowicz等[12]的研究结果与本研究结果存在差异,这可能与团聚体粒径大小、孔隙分布等因素有关。本研究结果表明,干土导热率与小团聚体比例呈负相关,说明干土导热率与黏粒含量存在密切关系[12, 19, 23]。

土壤导热率变化值用于反映土壤热量传递能力变化对水分的响应程度。本研究中,含大、中团聚体比例高的土壤导热率变化对水分的响应高于含小团聚体比例高的土壤。Adhikari等[24]发现土壤导热率随有机质含量增加而下降。本研究表明,土壤导热率变化速率与有机质含量呈负相关,这说明团聚体中的有机质含量会改变土壤热量的传递[4]。作为土壤固相的重要组成部分,土壤有机质作为团聚矿物颗粒的胶结剂,在土壤团聚体表面形成较厚的疏水有机层[7, 25],使得含有高有机质的大团聚体表面不易形成水膜,同时也可能减缓了水分填充大团聚体内部孔隙的速率,进而影响土壤热量的传递速率。此外,根据土壤团聚体“涂层”模型理论,铁氧化物通过吸附与胶结作用覆盖矿物颗粒表面,形成小粒径团聚体[25],增加了固体颗粒的比表面积,促进小粒径团聚体颗粒形成静电引力,有利于水分子在小团聚体周围形成水膜,增加固/固的接触面积,便于土壤导热[9, 19, 26]。

在田间尺度下,土壤常为水分非饱和状态。本研究中,S25-50-25或S50-25-25处理的非饱和土壤导热率最低,说明适宜的团聚体配比有利于农田土壤热量的储存,这在关于生物质炭和有机肥施用对土壤热量分配影响的研究结果中也得到证实[27-28]。在大、中、小团聚体配比适宜的情况下,适量小粒径颗粒(< 0.053 mm)如黏粒进入大孔隙中,可阻断充气孔隙的连续性,降低孔隙连通性和孔喉直径,影响水分在孔隙间的迁移,进而提高土壤的保墒保温能力[2, 6, 14, 28]。因此,通过采用优化土壤团聚体组分、改善土壤孔隙结构的土壤管理措施(如施用有机肥、生物质炭),能够稳定土壤水热环境,增强土壤对气温突变的抗逆能力[28-29]。

4 结论1) 不同团聚体粒径分布下,土壤导热率与水分饱和度之间的关系符合指数函数模型。

2) 团聚体粒径分布是土壤导热能力的影响因素,与含水率存在互作效应。干土导热率随小团聚体比例增加而下降;在非饱和土壤中,S25-50-25或S50-25-25配比土壤导热率最低,归因于土壤导热率变化值率与大、中团聚体比例和土壤有机质含量存在密切关系。

3) 优化土壤团聚体配比、提升土壤有机质含量的管理措施可以稳定土壤热状况,增强土壤抗热能力。长期施用有机肥土壤形成了适宜土壤蓄热的团聚体配比,有利于稳定气温骤变下的土壤温度。

| [1] |

Usowicz B, Lipiec J. The effect of exogenous organic matter on the thermal properties of tilled soils in Poland and the Czech Republic[J]. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2020, 20(1): 365-379 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Xiu L Q, Zhang W M, Wu D, et al. Heat storage capacity and temporal-spatial response in the soil temperature of albic soil amended with maize-derived biochar for 2 years[J]. Soil and Tillage Research, 2021, 205: 104762 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Haque M A, Ku S, Haruna S I. Soil thermal properties: Influence of no-till cover crops[J]. Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 2024, 104(3): 246-256 (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Abu-Hamdeh N H, Reeder R C. Soil thermal conductivity effects of density, moisture, salt concentration, and organic matter[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2000, 64(4): 1285-1290 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

王月月, 任图生. 玉米农田行尺度土壤热特性变异特征及其对土壤含水量和温度的响应[J]. 土壤, 2024, 56(2): 415-424 DOI:10.13758/j.cnki.tr.2024.02.022 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Fu Y W, Ghanbarian B, Horton R, et al. New insights into the correlation between soil thermal conductivity and water retention in unsaturated soils[J]. Vadose Zone Journal, 2024, 23(1): e20297 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

刘亚龙, 王萍, 汪景宽. 土壤团聚体的形成和稳定机制: 研究进展与展望[J]. 土壤学报, 2023, 60(3): 627-643 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Singh N, Kumar S, Udawatta R P, et al. X-ray micro-computed tomography characterized soil pore network as influenced by long-term application of manure and fertilizer[J]. Geoderma, 2021, 385: 114872 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Yudina A, Kuzyakov Y. Dual nature of soil structure: The unity of aggregates and pores[J]. Geoderma, 2023, 434: 116478 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Tian S Y, Zhu B J, Yin R, et al. Organic fertilization promotes crop productivity through changes in soil aggregation[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2022, 165: 108533 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

荣慧, 房焕, 张中彬, 等. 团聚体大小分布对孔隙结构和土壤有机碳矿化的影响[J]. 土壤学报, 2022, 59(2): 476-485 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Usowicz B, Lipiec J, Usowicz J B, et al. Effects of aggregate size on soil thermal conductivity: Comparison of measured and model-predicted data[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2013, 57(2): 536-541 (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Ju Z Q, Ren T S, Hu C S. Soil thermal conductivity as influenced by aggregation at intermediate water contents[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2011, 75(1): 26-29 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

邸佳颖, 刘晓娜, 任图生. 原状土与装填土热特性的比较[J]. 农业工程学报, 2012, 28(21): 74-79 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

刘志鹏, 徐杰男, 佘冬立, 等. 添加生物质炭对土壤热性质影响机理研究[J]. 土壤学报, 2018, 55(4): 933-944 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Johansen O. Thermal conductivity of soils[M]. Trondheim: University of Science and Technology Trondheim, 1975.

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Lu S, Ren T S, Gong Y S, et al. An improved model for predicting soil thermal conductivity from water content at room temperature[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2007, 71(1): 8-14 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

苏李君, 王全九, 王铄, 等. 基于土壤物理基本参数的土壤导热率模型[J]. 农业工程学报, 2016, 32(2): 127-133 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Schjønning P. Thermal conductivity of undisturbed soil– Measurements and predictions[J]. Geoderma, 2021, 402: 115188 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Zhang T, Cai G J, Liu S Y, et al. Investigation on thermal characteristics and prediction models of soils[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2017, 106: 1074-1086 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Radhakrishna H S, Chu F Y, Boggs S A. Thermal stability and its prediction in cable backfill soils[J]. IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems, 1980, PAS-99(3): 856-867 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Zhang M Y, Bi J, Chen W W, et al. Evaluation of calculation models for the thermal conductivity of soils[J]. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 2018, 94: 14-23 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Zhang M Y, Lu J G, Lai Y M, et al. Variation of the thermal conductivity of a silty clay during a freezing-thawing process[J]. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2018, 124: 1059-1067 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Adhikari P, Udawatta R P, Anderson S H. Soil thermal properties under prairies, conservation buffers, and corn–soybean land use systems[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2014, 78(6): 1977-1986 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Kleber M, Sollins P, Sutton R. A conceptual model of organo-mineral interactions in soils: Self-assembly of organic molecular fragments into zonal structures on mineral surfaces[J]. Biogeochemistry, 2007, 85(1): 9-24 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Regelink I C, Stoof C R, Rousseva S, et al. Linkages between aggregate formation, porosity and soil chemical properties[J]. Geoderma, 2015, 247: 24-37 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Gao Y, Li T X, Fu Q, et al. Biochar application for the improvement of water-soil environments and carbon emissions under freeze-thaw conditions: An in situ field trial[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2020, 723: 138007 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Miller J J, Beasley B W, Drury C F, et al. Influence of long-term feedlot manure amendments on soil hydraulic conductivity, water-stable aggregates, and soil thermal properties during the growing season[J]. Canadian journal of Soil Science, 2018, 98(3): 421-435 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

任立军, 李金, 邹洪涛, 等. 生物有机肥配施化肥对设施土壤养分含量及团聚体分布的影响[J]. 土壤, 2023, 55(4): 756-763 DOI:10.13758/j.cnki.tr.2023.04.008 (  0) 0) |

2. Jiangsu Yanjiang Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Nantong, Jiangsu 226541, China

2025, Vol. 57

2025, Vol. 57